Where Will the Bombs Hit Next?

Rain bombs are coming, and they’ll hit land with not only more frequency but more force. Officially labeled wet microbursts, the highly intense and destructive blasts of water will strike communities which are completely unprepared, according to scientists. “We need to recognize that we’re moving into a new climate, and our communities are built for an old climate, one that no longer exists,” says Chip Fletcher, a professor of geology and geophysics at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

On April 14th and 15th, the so-called rain bombs slammed into parts of Hawaii in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, dropping 50 inches of rain in 24 hours on the island of Kauai. The extreme rainfall caused widespread damage in the communities of Wainiha and Haena along the northern shore of Kauai. Locals said they had never experienced anything like it.

A river, called the Hanalei, not only flooded its banks but also carved a new course sweeping homes, cars, and livestock out to sea. In addition, a series of large landslides cut off access to the area, blocking the only road, called Kuhio Highway. “This is the most severe rain event in Hawaii that we know about since we started keeping records in 1905,” says Kawika Winter, a natural resources manager and the executive director of the renowned Limahuli Garden and Preserve, in Haena.

Communities Must Adapt to Rising Sea Levels

Climate Change

But this extremely severe rainfall is, in addition, something new and more ominous. It is Hawaii’s first major storm attributed completely to climate change. Both Fletcher and Winter, who study weather patterns in the Pacific Islands, cite the role of the planet’s increasingly warmer atmosphere in creating a new kind of massive, unstable weather system dropping rain bombs from the sky. “In the Pacific Islands, we don’t have the luxury of debating whether climate change is real,” says Winter. “Climate change already is affecting us, and it has been affecting us for some time.”

To Winter, the effects of climate change in Hawaii are the same as they are in other parts of the world, including, for instance, the state of California, which has been the site of its own highly destructive floods and landslides recently. In fact, scientists now believe that in California climate change is driving a cycle of weather conditions which will become increasingly volatile over time. In this cycle, the state will swing, in dramatic fashion, between floods and droughts in the coming years.

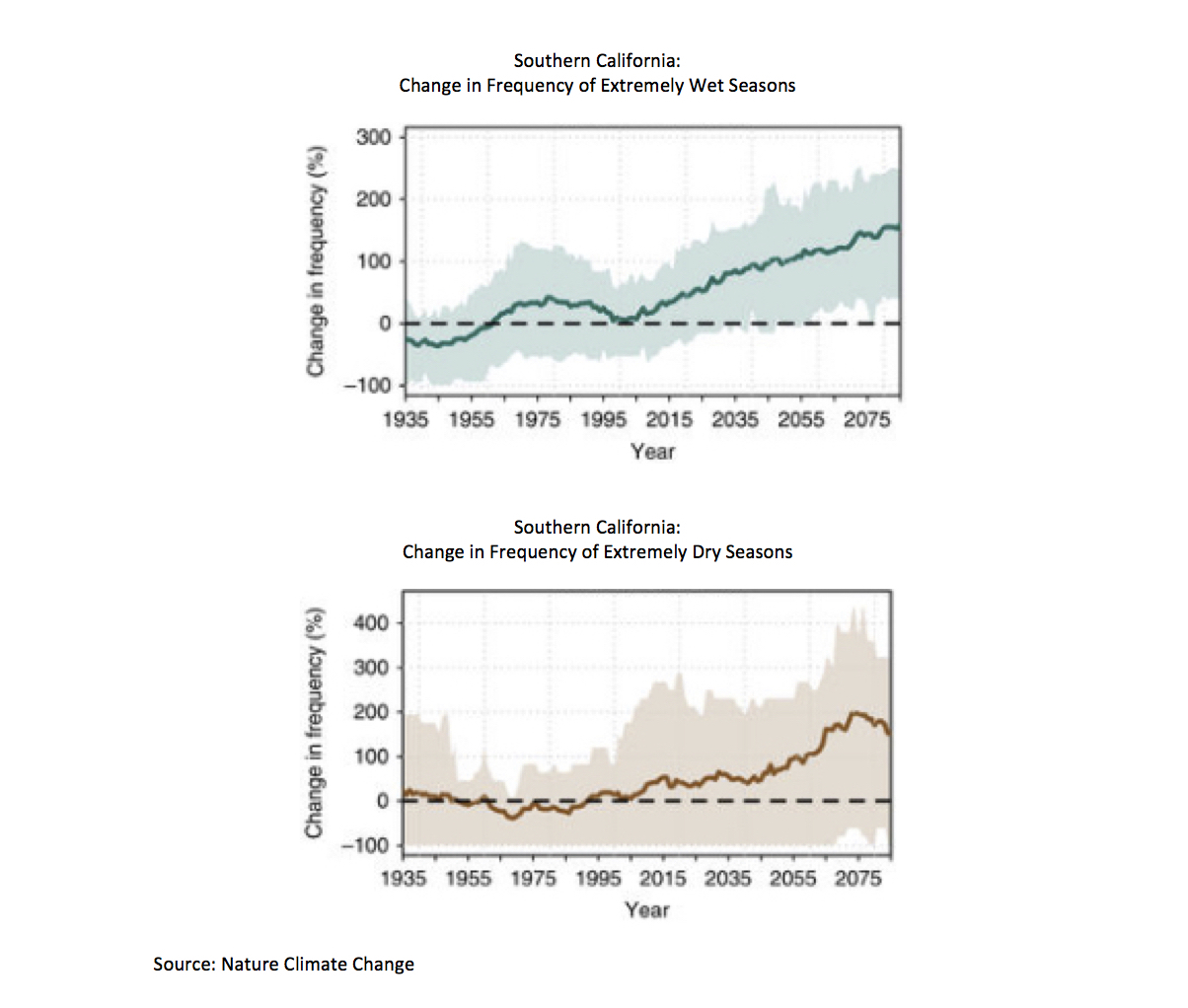

At the end of April, scientists at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) released the results of a new analysis of the effects of climate change on the state, predicting a future of dramatic weather swings for the southern part of the state, in particular. The frequency of very wet seasons will increase by 150 percent while the frequency of very dry years will rise by 200 percent, according to the scientists. “We see a big increase in extremes,” says David Swain, the lead scientist.

Floods to Droughts

Swain warns of a high probability of extreme rainfall which will cause flood waters to race across the Los Angeles metropolitan area and other major urban areas of the state of California in the next 40 years. At the same time, the UCLA scientist does not believe it is possible to exaggerate the magnitude of the destruction which will be caused by rushing flood waters. “We really need to be thinking seriously about what we’re going to do,” he says.

But Swain and his colleagues are well aware of the immensity of the challenge which is bearing down on California residents. Not only must they meet increasingly urgent requirements for controlling water and averting disastrous floods during periods of extreme rainfall. Also, simultaneously, they must meet increasingly urgent requirements for capturing water and storing it for use in periods of prolonged drought.

“Climate change is creating a water-storage problem for California,” says Alex Hall, a UCLA climate scientist and co-author of the recent study.

The Need for Water Storage in California Is Great

Monster Challenge

How will we meet the monster challenge? The obvious answer is to solve each one of its component problems. For the water-storage problem in California, UCLA’s Hall recommends new initiatives to replenish the basins holding ground water in various locations across the state.

But, of course, it won’t be easy; also, it won’t be cheap; and, finally, it will take time. Meanwhile, the next monster storm will hit, dropping rain bombs from the sky. In Hawaii, this realization is still setting in. “People have been describing this latest storm as a 100-year flood,” says Winter, the natural resources manager on the island of Kauai. “But it’s more likely that the next one is just a few years off, given the reality of climate change.”

Winter points out that, when a monster storm hits, it forces people into action. “In the end, communities have to fend for themselves,” says Winter, who emphasizes the importance of community resilience. “How we re-build could be an example for others.”